From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Jinn (disambiguation).

"Genie", "Jinnī", and "Djinn" redirect here. For other uses, see Genie (disambiguation), Jinnī (disambiguation), and Djinn (disambiguation).

| It has been suggested that Jinn in popular culture be merged into this article or section. (Discuss) Proposed since January 2011. |

The Majlis al-Jinn cave in Oman, literally "Meeting place of the Jinn". It is one of the world's biggest cave chambers.

The jinn are mentioned frequently in the Quran, and the 72nd sura of the Quran is entitled Sūrat al-Jinn.

[edit] Etymology and definitions

Jinn is a noun of the collective number in Arabic literally meaning "hidden from sight", and it derives from the Arabic root ǧ-n-n meaning "to hide" or "be hidden". Other words derived from this root are maǧnūn 'mad' (literally, 'one whose intellect is hidden'), ǧunūn 'madness', and ǧanīn 'embryo, fetus' ('hidden inside the womb').[4]The Arabic root ǧ-n-n means 'to hide, conceal'. A word for garden or Paradise, جنّة ǧannah, is a cognate of the Hebrew word גן gan 'garden', derived from the same Semitic root. In arid climates, gardens have to be protected against desertification by walls; this is the same concept as in the word "paradise" from pairi-daêza, an Avestan word for garden that literally means 'having walls built around'. Thus the protection of a garden behind walls implies its being hidden from the outside. Arabic lexicons such as Edward William Lane's Arabic-English Lexicon define ǧinn not only as spirits, but also anything concealed through time, status, and even physical darkness.[5]

The word genie in English is derived from Latin genius, meant a sort of tutelary or guardian spirit thought to be assigned to each person at their birth. English borrowed the French descendant of this word, génie; its earliest written attestation in English, in 1655, is a plural spelled "genyes." The French translators of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights used génie as a translation of jinnī because it was similar to the Arabic word in sound and in meaning. This use was also adopted in English and has since become dominant.[citation needed]

Many cultural interpretations noted the Jinn as having distinct male and females, they would often appear wearing vests and sashes, various interpretations note that they tied their hair long vertically. According to various stories Jinn could exist independently or bound to any particular object.

In Arabic, the word ǧinn is in the collective number, translated in English as plural (e.g., "several genies"); ǧinnī is in the singulative number, used to refer to one individual, which is translated by the singular in English (e.g., "one genie"). Therefore, the word 'jinn' in English writing is treated as a plural.

[edit] Jinn in the pre-Islamic era

Jinn from the One thousand and one nights.

Inscriptions found in Northwestern Arabia seem to indicate the worship of jinn, or at least their tributary status. For instance, an inscription from Beth Fasi'el near Palmyra pays tribute to the "Jinnaye", the "good and rewarding gods".[6]

In the following verse, the Quran rejects the worship of jinn and stresses that only God should be worshipped:

"Yet, they join the jinns as partners in worship with Allah, though He has created them (the jinns), and they attribute falsely without knowledge sons and daughters to Him. Be He Glorified and Exalted above (all) that they attribute to Him." (Quran 6:100)

In the One Thousand and One Nights several types of Jinn are depicted that coexist and interact with Humans: šayṭān, the Ghoul, the Marid, the Ifrit, and the Angels. The One Thousand and One Nights seems to present Ifrits as the most massive and strongest forms of Jinn and Marids are a type of Jinn associated with seas and oceans.

[edit] Jinn in Islam

In Islamic theology jinn are said to be creatures with free will, made from smokeless fire by Allah as humans were made of clay, among other things.[7] According to the Quran, jinn have free will, and ʾIblīs abused this freedom in front of Allah by refusing to bow to Adam when Allah ordered angels and jinn to do so. For disobeying Allah, he was expelled from Paradise and called "Šayṭān" (Satan). Jinn are frequently mentioned in the Quran: Surah 72 (named Sūrat al-Jinn) is named after the jinn, and has a passage about them. Another surah (Sūrat al-Nās) mentions jinn in the last verse.[8] The Quran also mentions that Muhammad was sent as a prophet to both "humanity and the jinn," and that prophets and messengers were sent to both communities.[9][10]Similar to humans, jinn have free will allowing them to do as they choose (such as follow any religion). They are usually invisible to humans, and humans do not appear clearly to them. Jinn have the power to travel large distances at extreme speeds and are thought to live in remote areas, mountains, seas, trees, and the air, in their own communities. Like humans, jinn will also be judged on the Day of Judgment and will be sent to Paradise or Hell according to their deeds.[11]

[edit] Classifications and characteristics

The social organization of the jinn community resembles that of humans; e.g., they have kings, courts of law, weddings, and mourning rituals.[12] A few traditions (hadith), divide jinn into three classes: those who have wings and fly in the air, those who resemble snakes and dogs, and those who travel about ceaselessly.[13] Other reports claim that ‘Abd Allāh ibn Mas‘ūd (d. 652), who was accompanying Muhammad when the jinn came to hear his recitation of the Quran, described them as creatures of different forms; some resembling vultures and snakes, others tall men in white garb.[14] They may even appear as dragons, onagers, or a number of other animals.[15] In addition to their animal forms, the jinn occasionally assume human form to mislead and destroy their human victims.[16] Certain hadiths have also claimed that the jinn may subsist on bones, which will grow flesh again as soon as they touch them, and that their animals may live on dung, which will revert to grain or grass for the use of the jinn flocks.[17]Ibn Taymiyyah believed the jinn were generally "ignorant, untruthful, oppressive and treacherous,"[18] thus representing the very strict interpretations adhered by the Salafi schools of thought.

Ibn Taymiyyah believes that the jinn account for much of the "magic" perceived by humans, cooperating with magicians to lift items in the air unseen, delivering hidden truths to fortune tellers, and mimicking the voices of deceased humans during seances.[18]

In Surah Al-Rahman (ayah 33) of the Muslim Quran, Allah reminds Jinn as well as mankind that should 'when' they possess the ability to pass beyond the furthest reaches of space, then it is only by His authority shall they be able to pass. Then it goes on to say, “Then which of the favors of your Lord do you deny?” In Surah Al-Jinn (ayahs 8 to 10) it is narrated by Allah concerning the Jinn how they touched or ‘sought the limits’ of the sky 'space' and found it full of stern guards and shooting stars, as a warning to man. It goes on further to say how they ‘the Jinn’ used to take stations in the skies to listen to divine decrees passed down through the ranks of the Angels, but those who attempt to listen now (during and after the revelation of the Quran) shall find fiery sentinels awaiting them.

[edit] Qarīn

A related belief is that every person is assigned one's own special jinnī, also called a qarīn, of the jinn that whisper to people's souls and tell them to submit to evil desires.[19][20][21] The notion of a qarīn is not universally accepted amongst all Muslims, but it is generally accepted that Šayṭān whispers in human minds, and he is assigned to each human being.In a hadith recorded by Muslim, the companion Ibn Mas'ud reported: 'The Prophet Muhammad said: 'There is not one of you who does not have a jinn appointed to be his constant companion (qarīn).' They said, 'And you too, O Messenger of Allah?' He said, 'Me too, but Allah has helped me and he has submitted, so that he only helps me to do good.' '

[edit] Jinn in Muslim cultures

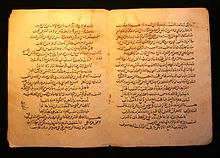

A manuscript of the One Thousand and One Nights.

More acclaimed stories of the Jinn can be found in the One Thousand and One Nights story of the Fisherman and the Jinni;[22] more than three different types of Jinn are described in the story of Maruf the Cobbler;[23][24] a mighty Jinni helps young Aladdin in the story of Alladin and the Wonderful Lamp;[25] as Hassan Badr ad-Din weeps over the grave of his father until sleep overcomes him he is awoken by a large group of sympathetic Jinni in the Tale of Ali Nur ad-Din and his son Badr ad-Din Hassan.[26]

During the Rwandan genocide both Hutus and Tutsi avoided searching in local Rwandan Muslim neighborhoods and widely believed myths that local Muslims and Mosques were protected by the power of Islamic magic and the efficacious Jinn. In Cyangugu, arsonists ran away instead of destroying the Mosque because they believed Jinn were guarding the Mosque and feared their wrath.[27]

[edit] Relationship of King Solomon and the genies

Main article: Islamic view of Solomon

According to traditions, the jinn stood behind the learned humans in Solomon's court, who in turn, sat behind the prophets. The jinn remained in the service of Solomon, who had placed them in bondage, and had ordered them to perform a number of tasks."And before Solomon were marshalled his hosts,- of jinn and men and birds, and they were all kept in order and ranks." (Quran 27:17)

The Quran relates that Solomon died while he was leaning on his staff. As he remained upright, propped on his staff, the jinn thought he was still alive and supervising them, so they continued to work. They realized the truth only when Allah sent a creature to crawl out of the ground and gnaw at Solomon's staff until his body collapsed. The Quran then comments that if they had known the unseen, they would not have stayed in the humiliating torment of being enslaved.

"Then, when We decreed (Solomon's) death, nothing showed them his death except a little worm of the earth, which kept (slowly) gnawing away at his staff: so when he fell down, the jinn saw plainly that if they had known the unseen, they would not have tarried in the humiliating Penalty (of their Task)." (Quran 34:14)

[edit] Difference in perception of jinn between East and West

There is a significant difference in how these beings are perceived in East (as jinn) and in West (as genies), which is evident in the two separate articles for these terms. Western natives moving to Eastern countries may experience a bout of culture shock when they are confronted with the presence of jinn and the people who believe in them, and two good examples of the struggle to adapt to a culture which believes in jinn are The Caliph's House and In Arabian Nights by Tahir Shah, which describe his family's experiences in moving from London to a jinn-inhabited home in Morocco.[edit] Existence and usage of jinn in other cultures

Genie in Legoland.

[edit] Jinn in the Bible

In Judeo-Christian tradition, the word or concept of jinn as such does not occur in the original Hebrew text of the Bible, but the Arabic word ǧinn is often used in several old Arabic translations.In several verses in those Arabic translations, the words: Jinn (جن) Jann (الجان al-Ǧān) Majnoon (مجنون Maǧnūn) and ʾIblīs (إبلیس) are mentioned as translations of familiar spirit or אוב (ob) for Jann and the devil or δαιμόνιον (daimónion) for ʾIblīs.

In Van Dyck's Arabic translation of the Bible, these words are mentioned in Leviticus 19:31, Lev 20:6, 1 Samuel 28:3, 1 Sa 28:9, 1 Sa 28:7, 1 Chronicles 10:13, Gospel of Matthew 4:1, Mat 12:22, Gospel of Luke 4:5, Luk 8:12, Gospel of John 8:44 and other verses[citation needed] as well. Also, in the apocryphal book Testament of Solomon, Solomon describes particular demons whom he enslaved to help build the temple, the questions he put to them about their deeds and how they could be thwarted, and their answers, which provide a kind of self-help manual against demonic activity.

[edit] Protection from jinn

An amulet, talisman or what is referred to as a tawiz amongst Sufi circles is a form of protection against many forms of spiritual evil, including protection against the jinn. It is often worn around the neck in a pouch, close to the heart. One such popular amulet was said to have been given to Sheikh Abdullah Daghistani by Muhammad in a vision. In that vision he was instructed to give this amulet to people as a protection for them in the last days. The amulet contains a depiction of the Throne Room of Allah. The amulet contains theosophic names as well as the names of folk saints. It is widely held to be very miraculous and a protection to those who submit to Allah.[citation needed]. It is to be noted that Muslims believe that all protection and help only comes from Allah, as it is a central Islamic tenet to believe that there is no power nor might save God's. Often, these sorts of practices are not widespread in the Islamic world and are mostly limited to certain tribal communities in remote areas. Muslims faithfuls believe that reciting the Verse of the Throne (Qur'an 2:255) and the final three concise chapters of the Qur'an (chapters 112-114), are the most effective means of seeking protection from satanic whispers and evil creatures.Other modern methods of avoiding trouble from the jinn include leaving them food and charcoal to keep them happy, asking permission before turning on water (as some people believe that the jinn live in water pipes), and sprinkling salt on the floor around one's bed to avoid nocturnal attacks by jinn.[citation needed]. These beliefs are most likely cultural perceptions rather than religious-based practices. It is noteworthy to mention that in the legal sources of Islam nothing is mentioned about the mentioned practices and rituals.

[edit] Other references to jinn in popular culture

In Neil Gaiman's novel American Gods, a salesman discontented with his life has a sexual encounter with a jinn (specifically, an ifrit) who is working as a taxi driver in New York.[edit] See also

- Arabian mythology

- Genius loci

- Ghoul

- Grine

- Houri

- Ifrit (a class of infernal jinn)

- Jinn in popular culture

- Marid (jinn associated with open sea waters)

- One Thousand and One Nights

- Qareen

- Shaytan

- Winged genie

- Yazata

[edit] References

- ^ Qur’ān 15:27

- ^ Qur’ān 55:31

- ^ El-Zein, Amira. "Jinn," 420-421, in Meri, Joseph W., Medieval Islamic Civilization - An Encyclopedia.

- ^ Wehr, Hans (1994). Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (4 ed.). Urbana, Illinois: Spoken Language Services. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-87950-003-0.

- ^ Edward William Lane’s Arabic Lexicon

- ^ Hoyland, R. G., Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam.

- ^ Quran 55:14–15

- ^ Quran 116:4–4

- ^ Quran 51:56–56

- ^ Muḥammad ibn Ayyūb al-Ṭabarī, Tuḥfat al-gharā’ib, I, p. 68; Abū al-Futūḥ Rāzī, Tafsīr-e rawḥ al-jenān va rūḥ al-janān, pp. 193, 341

- ^ Tafsīr; Bakhsh az tafsīr-e kohan, p. 181; Loeffler, p. 46

- ^ Ṭūsī, p. 484; Fozūnī, p. 527

- ^ Fozūnī, p. 526

- ^ Fozūnī, pp. 525–526

- ^ Kolaynī, I, p. 396; Solṭān-Moḥammad, p. 62

- ^ Mīhandūst, p. 44

- ^ Abu’l-Fotūḥ, XVII, pp. 280–281

- ^ a b Ibn Taymiyyah, al-Furqān bayna awliyā’ al-Raḥmān wa-awliyā’ al-Shayṭān ("Essay on the Jinn"), translated by Abu Ameenah Bilal Phillips

- ^ Quran 72:1–2

- ^ Quran 15:18–18

- ^ Sahih Muslim, No. 2714

- ^ http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/arabian/bl-arabian-jinni.htm

- ^ http://www.scribd.com/doc/53819003/47/Maruf-the-Cobbler

- ^ http://www.wollamshram.ca/1001/Vol_10/tale169.htm

- ^ http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/arabian/bl-arabian-alladin.htm

- ^ http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/arabian/bl-arabian-nuraldin.htm

- ^ Kubai, Anne (April 2007). "Walking a Tightrope: Christians and Muslims in Post-Genocide Rwanda". Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations (Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group) 18 (2): 219–235. doi:10.1080/09596410701214076.

- ^ Guanche Religion

| This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (June 2012) |

- Al-Ashqar, Dr. Umar Sulaiman (1998). The World of the Jinn and Devils. Boulder, CO: Al-Basheer Company for Publications and Translations.

- Barnhart, Robert K. The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. 1995.

- "Genie”. The Oxford English Dictionary. Second edition, 1989.

- Abu al-Futūḥ Rāzī, Tafsīr-e rawḥ al-jenān va rūḥ al-janān IX-XVII (pub. so far), Tehran, 1988.

- Moḥammad Ayyūb Ṭabarī, Tuḥfat al-gharā’ib, ed. J. Matīnī, Tehran, 1971.

- A. Aarne and S. Thompson, The Types of the Folktale, 2nd rev. ed., Folklore Fellows Communications 184, Helsinky, 1973.

- Abu’l-Moayyad Balkhī, Ajā’eb al-donyā, ed. L. P. Smynova, Moscow, 1993.

- A. Christensen, Essai sur la Demonologie iranienne, Det. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser, 1941.

- R. Dozy, Supplément aux Dictionnaires arabes, 3rd ed., Leyden, 1967.

- H. El-Shamy, Folk Traditions of the Arab World: A Guide to Motif Classification, 2 vols., Bloomington, 1995.

- Abū Bakr Moṭahhar Jamālī Yazdī, Farrokh-nāma, ed. Ī. Afshār, Tehran, 1967.

- Abū Jaʿfar Moḥammad Kolaynī, Ketāb al-kāfī, ed. A. Ghaffārī, 8 vols., Tehran, 1988.

- Edward William Lane, An Arabic-English Lexicon, Beirut, 1968.

- L. Loeffler, Islam in Practice: Religious Beliefs in a Persian Village, New York, 1988.

- U. Marzolph, Typologie des persischen Volksmärchens, Beirut, 1984. Massé, Croyances.

- M. Mīhandūst, Padīdahā-ye wahmī-e dīrsāl dar janūb-e Khorāsān, Honar o mordom, 1976, pp. 44–51.

- T. Nöldeke "Arabs (Ancient)," in J. Hastings, ed., Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics I, Edinburgh, 1913, pp. 659–73.

- S. Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, rev. ed., 6 vols., Bloomington, 1955.

- S. Thompson and W. Roberts, Types of Indic Oral Tales, Folklore Fellows Communications 180, Helsinki, 1960.

- Solṭān-Moḥammad ibn Tāj al-Dīn Ḥasan Esterābādī, Toḥfat al-majāles, Tehran.

- Moḥammad b. Maḥmūd Ṭūsī, Ajāyeb al-makhlūqāt va gharā’eb al-mawjūdāt, ed. M. Sotūda, Tehran, 1966.

[edit] Further reading

- Crapanzano, V. (1973) The Hamadsha: a study in Moroccan ethnopsychiatry. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press.

- Drijvers, H. J. W. (1976) The Religion of Palmyra. Leiden, Brill.

- El-Zein, Amira (2009) Islam, Arabs, and the intelligent world of the Jinn. Contemporary Issues in the Middle East. Syracuse, NY, Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3200-9.

- El-Zein, Amira (2006) "Jinn". In: J. F. Meri ed. Medieval Islamic civilization – an encyclopedia. New York and Abingdon, Routledge, pp. 420–421.

- Goodman, L.E. (1978) The case of the animals versus man before the king of the Jinn: A tenth–century ecological fable of the pure brethren of Basra. Library of Classical Arabic Literature, vol. 3. Boston, Twayne.

- Maarouf, M. (2007) Jinn eviction as a discourse of power: a multidisciplinary approach to Moroccan magical beliefs and practices. Leiden, Brill.

- Zbinden, E. (1953) Die Djinn des Islam und der altorientalische Geisterglaube. Bern, Haupt.

[edit] External links

| Look up genie in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Jinn. |

No comments:

Post a Comment